Paul Klee

at Tate Modern: Making Visible 2013/2014

Paul Klee 1921

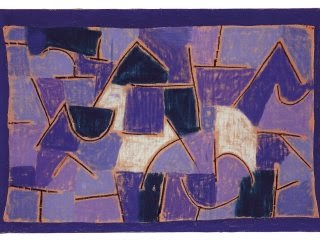

No other artist of the twentieth century made marks, lines and doodles

sing with quite the same melody as Paul Klee. As a result, you’ll spend ages

peering at and poring over the witty, joyful masterpieces in this

career-spanning retrospective of the Swiss-German artist, watching Klee’s ideas

spring to life on canvas and on tiny sheets of paper that become flickering

constellations. It's hard to imagine now that his intricate, fantastical art

was regarded as 'degenerate' by the Nazis in the early1930s. At that time, Klee

was teaching at the Düsseldorf Academy. When he returned to his native Bern in

Switzerland in 1933, his work became darker in tone, reflecting the

deteriorating political situation and his severe illness – diagnosed as

scleroderma in 1936.

Blue Night 1937

The Tate's exhibition challenges Klee’s reputation as a whimsical

dreamer – famous for describing drawing as being like 'taking a line for a walk

– drawing attention to the rigour with which he recorded and catalogued his

work throughout his career. We can’t time-travel to enter Klee’s studio and see

how his works progressed but, in offering up paintings made in sequence, Tate

Modern’s show gives us the next best thing. Moving through the exhibition is

like seeing a series of snapshots of Klee’s working life. You’ll discover how

paintings developed in tandem or relay, like the Tate’s famous watercolour

‘They’re Biting’, which is flanked by three works that precede it and one that

follows. Or how they may have been revisited and reworked over time, like ‘Akt

(Nude)’, which Klee started in 1910 but didn’t finish until 1924.

Tate’s reappraisal sheds light on dualities in Klee’s character. He was

a talented musician (he played the violin, often to make ends meet) as well as

an artist. He was also ambidextrous, painting and drawing with one hand while

writing with the other. This stunning show also reveals that, while there are

elements of cubism, surrealism and pointillism in his work, he was, above all,

an individualist. It leaves you with a sense of creative, personal enquiry

about the world that is uplifting and truly inspiring.

Static Dynamic Intensification

Paul Klee at Tate Modern:

curator interview(Matthew Gale) from Tate Modern

Paul Klee is forever associated with his famously quirky description of

drawing as ‘taking a line for a walk’. The stories about the Swiss-German

artist that have stuck since his death in 1940 are similar eccentric. There’s

the tale of his first day of teaching at the Bauhaus in 1921, when Klee, then

aged 41 and already well-known in Europe, is said to have backed through the

door of the classroom, avoiding eye contact with his students, drawn two arcs

on the blackboard and declared: ‘This is the fish of Columbus!'

Another anecdote from around 1930 – by the American art collector Edward MM

Warburg – places Klee in his Dessau studio. When the artist’s beloved cat Bimbo

ambles across the still-wet watercolours they are admiring, Warburg tries to

shoo it away. Klee, however, just laughs and says: ‘Many years from now, one of

your art connoisseurs will wonder how in the world I ever got that effect.’

Steps 1929

These accounts are of a piece with Klee’s endlessly innovative and

apparently effortless paintings and works on paper, with their flowing lines,

glowing patchworks of colour and whimsical depictions of animal, plant and sea

life.

‘Klee’s work is always about what it means to be in the world, how to process

it,’ says Matthew Gale, curator of the first Klee exhibition in London for more

than a decade. Yet, behind the freewheeling genius there was another,

altogether more obsessive side to this modern master. Throughout his career,

Klee used a variety of numbering systems – made up of the year, month and day –

as a way of documenting his prodigious output. His apparently spontaneous

creativity, which led to a total of 9,000 works being produced during his lifetime,

was always held in check by this analytical approach to numbering his work. It

was his way of revisiting what he had made, making sense of quickfire artistic

impulse.

Featuring around 200 paintings, Tate Modern’s new show foregrounds this

characteristic, using it to delve deep into Klee’s creative processes. ‘The way

in which the exhibition is structured derives from Klee’s own numbering system,

which he started in 1911,’ explains Gale. ‘The purpose is to show the

incredible diversity of his production.’

Comedy 1921

Museum exhibitions are great at presenting us with end results – those

polished, cherished icons of art history. They’re often less adept at revealing

how those results came into being. We can’t time-travel to enter Klee’s studio

and see how his works progressed but – in offering up paintings made in

sequence – Tate Modern’s show gives us the next best thing. Moving through the

exhibition is like seeing a series of snapshots of Klee’s working life. You’ll

discover how paintings developed in tandem or relay, like the Tate’s famous

watercolour ‘They’re Biting’ (1920), which is flanked by works that precede and

follow it.

Tate’s reappraisal sheds light on dualities in Klee’s character. He was a

talented musician (he played the violin, often to make ends meet) as well as an

artist. He was ambidextrous, painting and drawing with his left hand while

writing (and signing the work) with his right. ‘I think cataloguing the work

allows him to have a structure,’ explains Gale. ‘This clear, orderly side to

him means he can open the door of his studio and range freely as his

imagination allows him.’

If Klee is underappreciated in Britain, Gale puts it in part down to fashion:

‘We’ve passed through a sort of dip in his reputation and I hope that we’re

going to inspire a new generation to look at Klee in a different way.’ It may

also be due to the juggernaut of art history. While Picasso will forever be linked

with cubism, Matisse fauvism and Seurat pointillism, Klee’s fame may have

suffered from a lack of ties to any particular art movement. ‘“Isms” aren’t

everything,’ says Gale. ‘I think the fact that Klee isn’t associated with an

“ism” can make him difficult to categorise, but I think that is probably also

the strong point in his legacy – that he provides an example of an incredibly

rich creativity that’s not pigeonholed.

Full Moon 1933

Klee was

certainly celebrated in his lifetime, with a solo exhibition at the

Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 1921 and a retrospective at the Museum of Modern

Art, New York, in 1930. During the final decade of his life, Picasso and

Wassily Kandinsky came to pay tribute to the master in Bern, Switzerland, where

Klee took refuge after his work was deemed ‘degenerate’ by the Nazis and he was

dismissed from his teaching position in Düsseldorf.

By this time he had been diagnosed with scleroderma, a debilitating hardening

of the skin. Klee’s numbering of his work didn’t stop but his production became

erratic. In 1936, he produced just 25 works, while in 1939 he made more

than 1,000 paintings and drawings that ‘fell like leaves’ around him. The last

work he numbered in 1940, a leap year, is 366. ‘There seems something very

symbolic about stopping with that number as if he feels he’s completed that

year’s work,’ says Gale. ‘He clearly knew he was dying.’

While this casts a shadow over Klee’s later works, many of his final paintings

are defiantly upbeat, like the joyously rhythmic ‘Twilight Flowers’ (1940).

It’s this sense of playful enquiry about the world which Gale hopes visitors

will take away with them. ‘I think you’ll get a sense of the amazingly

productive journey he goes on, and go away inspired to make work yourself, in

whatever realm. Klee wrote, as well as playing the violin and painting, making

his own brushes and puppets for his son. His is not an exclusive sort of

creativity but one that encourages you to explore that creative part of your

life.’ Who knows, maybe you’ll even get the cat to take a line for a walk too.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Marcus Coates has proposed to place a large replica

of ‘The Eagle’, a rocky outcrop situated in Brimham Rocks, Yorkshire on the

plinth; Trafalgar Square is almost entirely fashioned from stone, sourced from

all over Britain and manipulated into buildings, pillars and statues by the

will of architects, designers and sculptors. Marcus Coates plans to contrast

these symbols of rational progress with a huge replica of a gritstone outcrop

created hundreds of millions of years ago in Yorkshire by the natural forces of

ice, wind and rain. Its form suggests a face or a bird, as we automatically try

to make sense of the organic shapes that emerge and retreat as we walk around

it, and invest it with human qualities or mythical powers. It would be a

monument to non-human creativity and a totem of timeless, irrepressible powers.

David Shigley’s design, Really Good, is a 10-metre-high thumbs-up,

cast in the same dark patina as the other statues in the square; A giant hand

in a thumbs-up gesture, and with a really long thumb at that, must mean that

something, somewhere, is really good. But what is that something and where is

it? Is it Trafalgar Square? Or all of London? Or maybe the artwork itself? And

if it’s so good, why is that? Who says so? And will we agree?

Hans Haacke has created a skeletal, riderless horse that will

display the live ticker of the London Stock Exchange on an electric ribbon tied

to its leg; Instead of the statue of William III astride a horse, as originally

planned for the empty plinth, Hans Haacke proposes a skeleton of a riderless,

strutting horse. Tied to the horse’s front leg is an electronic ribbon which

displays live the ticker of the London Stock Exchange. The horse is derived

from an etching by George Stubbs, whose studies of equine anatomy were

published the year after the birth of the reputedly decadent king, whose statue

was abandoned due to a lack of funds. Haacke’s proposal makes visible a number

of ordinarily hidden substructures, tied up with a bow as if a gift to all.

Liliane Lijn’s proposal shows two identical kinetic cones made of

brushed anodised aluminium engaged in a mesmerising dance; Rather than one

imposing sculptural object, Liliane Lijn’s proposal The Dance features

the complex changing relation between two apparently identical objects. The

cone is a ubiquitous abstract form that occurs in mathematical, mythical and

astronomical systems. Here the cones also relate to the spire of St.

Martin-in-the-Fields, while their gleaming metallic surfaces recall the

machinery of space travel. Once The Dance begins, formal geometry

gives way to sensual movement and we become mesmerised by the energy of the

interaction.

Ugo Rondinone’s Moon Mask is an aluminium, abstract sentinel facing

out over the square; Ugo Rondinone’s MOON MASK, modelled expressively by

hand, enlarged, cast in aluminium, and fixed to a pole, would be an abstract

sentinel facing out over the square. MOON MASK seemingly refers to many

visual traditions – perhaps the folk art of an ancient clan or early 20th

century Cubism, which was itself influenced by African tribal masks – and yet

it makes no specific claims for its origin. The eventual work would inspire

free association, its three window-like apertures suggesting portals through

which cultural references and individual emotions can tumble at will.

Mark Leckey has designed a creature made of amalgamated

elements of the permanent statues in Trafalgar Square, including details from

the statues of James II, Admiral Jellicoe, the water fountain, and the Fourth

Plinth itself. Mark Leckey has riffed on elements

traditionally found carved in marble or cast in bronze, including scrolls,

coats of arms and a sword in its scabbard for Larger Squat Afar (an

anagram of Trafalgar Square).

“I believe the proposal reflects how we now approach the world in the 21st century. Because of current technology, objects and artefacts are no longer these fixed, permanent things. Instead we look at any sculpture, object or image and ask, what can I do with that? How can I change it to suit my desires?”

Is All art Religious? Is all Religion Art?

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Fourth Plinth Commission 2014

Exhibition

of Proposals for the Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, London, to be exhibited

2014

St Martin-in-the-Fields 25th September to 17th

November 2013

Coates makes

videos, performances and installations that are in turn sublime and humorous,

asking audiences and participants to explore their imaginations in ways they

might not ordinarily. Communing with animal and bird spirits, emulating their

movements or transmitting their calls and cries, the artist attempts to answer

questions on how we can live in urban societies. His observations might strike

a chord with his audiences through metaphor, or through the sheer desire to

make sense of a disordered universe.

Really Good would be cast in bronze with the same dark patina as the other statues

in the Square, the comic extension of the thumb bringing it up to ten metres in

height. Shrigley’s ambition is that this will become a self-fulfilling

prophecy; that things considered ‘bad’, such as the economy, the weather and

society, will benefit from a change of consensus towards positivity.

Shrigley’s

daily tirade of satirical vignettes takes the British tradition of satire into

three and four dimensions. In his drawings and animations protagonists express

their dark impulses and are subject to the violence and irrationality of life,

while his sculptures are often jokes in 3D form, reflecting the absurdity

of contemporary society.

Haacke’s

early work employed physical and organic processes, such as condensation, in

what he called ‘systems’, until his focus shifted to the socio-political field

of equally interdependent dynamics. For the last four decades Haacke has been

examining relationships between art, power and money, and has addressed issues

of free expression and civic responsibilities in democratic societies. Haacke’s

practice is difficult to categorise, moving from object to image to text, from

painting to photography, at times of a provocative nature.

The shifting

shapes and interactions of The Dance are an extension of Lijn’s interest

in combining energy and matter, language and light. Her small and large-scale

kinetic installations often use technologies such as laser cutting,

programmable electronics and aerogel, a material used by NASA to capture

stardust. Lijn’s Poemcons and Poem Machines, rotating cones and

drums bearing evocative words and phrases, offer tantalising fragments of

meaning and insight, while ultimately falling apart in the mind.

Rondinone’s

preoccupation with time - at the cosmic scale as well as that of art history

and everyday experience - often finds form in abstract imagery intended to

connect the sublime with the everyday. His optically shimmering mandala

paintings, for example, re-use the geometric Buddhist symbol for eternity.

Elsewhere figures made from stacked, roughly hewn cubes of rock seem to express

an ancient sense of awe in the face of nature, while also offering a range

of contemporary readings from the psychological to the comical.

“I believe the proposal reflects how we now approach the world in the 21st century. Because of current technology, objects and artefacts are no longer these fixed, permanent things. Instead we look at any sculpture, object or image and ask, what can I do with that? How can I change it to suit my desires?”

Larger Squat Afar is an anagram of ‘Trafalgar Square’, and Mark Leckey’s chimera is

itself an amalgam of elements lifted from all the statues found in the square.

Details of James II, the water fountain, Admiral Jellicoe and the plinth itself

are enmeshed into a single figure, which, while appearing absurd illustrates

the compound history of both people and place. Fabricated using 3D laser

scanning and printing technology, Larger Squat Afar embodies the power

of the digital to overcome the physical and to fulfill the more monstrous

capacities of the human imagination.

Leckey

frequently looks to the mediated nature of public and private environments, in

which imagery is employed to transcend the mundane. Collage and animation

techniques are used in videos and sculptures, where the hidden is made

explicit, desires are expressed and obscure personal narratives are revealed.

It is digital platforms, above all else, that signal the contemporary for

Leckey, where even the inanimate object can appear to communicate to us at

will.

ARTIST

BIOGRAPHIES

Marcus

Coates

Born 1968 in

London. Lives and works in London.

Marcus

Coates makes videos, performances and installations that attempt to answer

questions about how we live in urban societies. He has had recent solo

exhibitions at South Alberta Gallery, Canada (2012); and Milton Keynes Gallery

(2010). Recent public art projects include Create London (2013) and Vision

Quest: a ritual for Elephant & Castle (2012). Coates has also performed at

Port Eliot Festival, Cornwall; Mori Art Museum, Tokyo; Kunsthalle Zurich;

Barbican Art Gallery, London; and Hayward Gallery, London.

Hans Haacke

Born 1936 in

Cologne. Lives and works in New York.

For the last

four decades Hans Haacke has been examining the relationships between art,

power and money, and has addressed issues of free expression and civic

responsibilities in democratic societies in his work. He works in many

different mediums including painting, photography and written text. He has had

recent solo exhibitions at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid

(2012); MIT List Visual Arts Centre, Cambridge, MA (2011); X-Initiative, New

York (2009); and Akademie der Künste, Berlin (2006). Haacke’s work has been

included in four Documentas and numerous biennials around the world. He shared

a Golden Lion Award with Nam June Paik for the best pavilion at the 45th Venice

Biennale (1993), and in 2000 he unveiled a permanent installation in the

Reichstag, Berlin.

Mark Leckey

Born 1964 in

Birkenhead. Lives and works in London.

Mark

Leckey’s work explores the mediated nature of public and private environments,

often working collage and animation techniques into his video and sculptural

work. He has had recent solo exhibitions at The Hammer museum, Los Angeles

(2013); Banff Centre, Alberta (2012); Serpentine Gallery, London (2011); Abrons

Art Centre, New York (2009); and Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne (2008). Leckey

curated the Hayward Touring show ‘The universal addressability of dumb things’

(2013) and was awarded the Turner Prize in 2008.

Liliane Lijn

Born 1939 in

New York. Lives and works in London.

Internationally

exhibited since the 1960s, with works in numerous collections including Tate,

the British Museum, and the V&A, and FNAC, Paris, Lijn is best known for

her kinetic sculptures and her work with language and light. Recent exhibitions

include Light Years at Sir John Soane’s Museum, London (2011); Gallery One, New

Visions Centre, Signals, Indica at Tate Britain, London (2012); Ecstatic

Alphabets/Heaps of Language at MoMA, New York (2012); and Cosmic Dramas, mima,

Middlesborough. Recent public commissions include Solar Beacon, a sci-art

installation of heliostats on the towers of the Golden Gate Bridge; and Light

Pyramid, a beacon for the Queen’s Jubilee, which was commissioned by Park Trust

and MK Gallery, Milton Keynes.

David

Shrigley

Born 1968 in

Macclesfield. Lives and works in Glasgow.

David

Shrigley’s work draws on the British tradition of satire, creating drawings,

animations and sculptures that reflect the absurdity of contemporary society.

He has had recent solo exhibitions at Bradford 1 Gallery (2013); Cornerhouse

Gallery (2012), Hayward Gallery, London (2012); Yerba Beuna Centre for the

Arts, San Francisco (2012); and Kelvingrove Museum, Glasgow (2010). Shrigley’s

Sort of Opera: Pass the Spoon was performed at Tramway, Glasgow, and Southbank

Centre, London (2011 – 12), and he has been nominated for the Turner Prize

2013.

Ugo

Rondinone

Born 1964 in

Brunnen, Switzerland. Lives and works in New York.

Ugo Rondinone

is a mixed-media artist whose work explores themes of fantasy and desire. He

has had recent solo exhibitions at M Museum, Leuven (2013); Art Institute of

Chicago (2013); Common Guild, Glasgow (2012); Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens

(2012); and Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau (2010). Rondinone has created public

commissions for the Rockefeller Plaza, New York; the IMB Building, New York;

and Louis Vuitton, Munich. He represented Switzerland in the 52nd Venice

Biennale (2007).

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Is All art Religious? Is all Religion Art?

God is Dead

Signs in Peckham

Christopher Clack

2011

Art as a Facilitator of Society.

Is all Art Religious?

Is all Religion Art?

These two over-simplified questions are not reversals of one

another.

In the first question

the term Art refers to not just those creative expressions of a society in

which all basic needs are met and there is time for recreation and

self-expression, but to the practices which have been associated by a

structured society to basic needs as well, such as the astrological

agricultural practices of the Ancient Egyptians. This requires a suitably developed social

structure which has had time to contemplate non-material explanations for

material or natural phenomena. Art in

the first question might also encompass methods which today are regarded as

occupying a field completely separate to Art, for example mathematical models

of the universe or alpha-numerical sequences of purported significance, the

most common, useful and contemporaneous of these, I propose to be the study of

Fractals, mathematical sets whereby patterns are the same at every scale or

nearly the same at different scales, vaguely comparable to infinite regression.

To be Religious, as the first question is phrased, does not

require that something is part of a formal structure or a recognised

Religion. The term encompasses a variety

of spiritual, ritualistic and pseudo-scientific phenomena which have parallels

across many societies, such as astronomy, idol worship and deification. Symbolism is a common theme in Art and

Religion.

In the second question, Art is a similar concept, but

whereas some Art is obviously apparent as itself, the paintings and mosaics of

churches around the globe for example, the term encompasses the written and

spoken word, the staging of events as managed theatrics, music and decorative

visual arts. In this second question

Religion does refer to formal structured religions.

It requires that all human beings have similar cognitive

processes and respond in predictable ways.

Neurotheology (a term from Huxley’s novel Island) is the study of the

brain and Religion, and the search for the God Spot. Responses to Religious stimuli are monitored,

but as the extent of any spiritual experience is entirely subjective and so the

studies are no more in depth than showing correlations. There has been research into an evolutionary

history for religion. Nicolas Wade, a

British science writer for the New York Times wrote,

“Like most behaviours that are found in societies throughout

the world, religion must have been present in the ancestral human population

before the dispersal from Africa 50,000 years ago. Although religious rituals

usually involve dance and music, they are also very verbal, since the sacred

truths have to be stated. If so, religion, at least in its modern form, cannot

pre-date the emergence of language. It has been argued earlier that language

attained its modern state shortly before the exodus from Africa. If religion

had to await the evolution of modern, articulate language, then it too would

have emerged shortly before 50,000 years ago.” (N. Wade. Before the Dawn.

Penguin Books 2006 .p.8 p.165)

It may be that religion conferred an evolutionary advantage

on those who followed it and it may therefore have been naturally selected

for. Advantages of religion may include

social cohesion and thus the elaborate and expensive (in terms of time, money,

danger etc.) individual religious practices and ceremonies show the extent of

an individual’s commitment to a group (Sosis, R.; Kress,

H. C.; Boster, J. S. (2007). "Scars for war: evaluating alternative signalling

explanations for cross-cultural variance in ritual costs". Evolution

and Human Behavior 28 (4): 234–247).

It is impossible to argue that Art is

cheap. One need only to wander into a

moderate village Church in the U.K. and if it was constructed before The

Reformation (the actions of Martin Luther in 1517 are seen as the starting

point in this) then it will have been constructed from and decorated with

expensive and elaborate materials. There

are famous examples around the globe of elaborate sacred sites.

There is, once we acknowledge the historical

significance of Religion even if it is not as evident today, a lot of power

tied up with, not only the physical wealth of, but also the administration of

Religion. In England the Bible was not

published in the language of the population until, at the earliest, the tenth

century, but it was not translated into Modern English until the early

sixteenth century when John Tyndale produced his widely distributed

version. This was also the first

press-printed Bible. Thus the work of translating the most important

theological ideas to the masses was in the power of an Elite. The use of visual representations of

interpreted scriptural messages was commonplace and thus Art was the language

of Religion. It is easy to believe that

those holding such sway over the masses would not wish to relinquish it but to

reinforce it through elaborate and mysterious ceremonies and so an

understanding of stage craft would be beneficial.

Today, in the UK, we inhabit an

increasingly Secular society and yet our brains are no different from those of

our forebears. Religion may be distant

from our lives but Art is almost inseparable from it. Unless we live in the most remote Crofting

community, I would suggest that daily life is awash with music, design,

architecture, photography and film. It

may be that sculpture and mass produced pictorial Art is not everywhere but it

is not hard to find and fine examples of original works, such as paintings and

sculpture have to be sought out by an individual but there is designated government

funding to make these works available to the public.

If Art is not required as a religious

tool anymore and, in general, the population is turning away from Religion,

then why should Art retain any importance to us? Is it a way to access the same basic emotions

associated with the human condition and the universal practical issues of

living in a society? As we academically

turn towards scientific explanations for material phenomena, we cannot accept

the teachings of Formal Religion, but we retain a need for what it provided us

with.

Art was a facilitator for this in the past exactly as it is now.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Reith Lectures 2013

Playing to the Gallery by Grayson Perry.

I have been following the career of Grayson Perry since the very moment I saw him on television in the early nineties. I was a schoolgirl, attending a convent school in a Cheshire village and contemporary art was not part of my life.

I saw Grayson Perry, as Claire, accepting the Turner Prize (of which I had never heard) and a different side of what might be sensible appeared to me. It wasn't a conscious decision to follow Mr Perry and it is only in recent years that I have gone out of my way to seek out his work, his exhibitions, but whenever he was mentioned I was interested.

He is a fascinating man. He has the confident authority of most successful artists, but he always seems to be lacking the arrogance of many of his peers. He might be odd, he might be married to his psychoanalyst, he might be many things, but I believe that he is a fascinating and humorous man ans I was was delighted when I heard he would be giving this year's series of Reith Lectures.

The following is not a transcript of the lectures but a summary of what I gain from listening to them.

1. Democracy has bad taste.

Grayson Perry inhabits the Art World. As an artist and lecturer and commentator on contemporary arts, he does not consider himself an expert but must indeed be a close approximation.

As an insider of the this rarefied world and in giving these lectures he tries to encourage people to engage with physical places where art is to be to found and to be comfortable.

Speaking primarily with regard to the visual arts, Grayson Perry considers museums, commercial galleries and the more introspective, historical artist-dealer-collector relationship. He dissects the 5.3million visitors per annum to the Tate Modern, one of the U.K.s most popular tourist destinations. These visitors have been split into categories, some of whom, Grayson argues, would be impossible to keep away and these include the 'Urban Arts Eclectic' and the 'Mature Explorers', but he addresses himself to the 36% of visitors categorised as 'Dinner and a Show' or 'Fun, Fashion and Friends'.

During the discourse, Insider, Mr Perry, recognises the intimidating nature of the gallery environment and tries to address this by providing the imagined visitor with a methodology of approaching the art to which they will be exposed and how to judge it on an alien scale of merit.

The issues of judging art and of deciding upon its quality are addressed as one and the same things, in most respects. For example the popularity of a piece of art does not mean it is of quality but an historically significant piece or one of aesthetic sophistication may become very popular and therefore valuable and will inevitably be of quality.

As humans looking at art we will all have many similar responses and many of these can be cultural. Several Russian artists surveyed the preferences of the public, across several countries, as regards contemporary art and discovered that most people prefer the colour blue. This is of course of no help to anyone but it is interesting nevertheless.

There is a language which surrounds the discussion of art which may be alienating to the general public and also unhelpful to artists themselves. An analysis of the website of art gallery press releases E Flux showed it contained very few nouns; Art English. This is a In the hundred years leading up to the 1970s, Grayson Perry argued, art became very self-conscious. This could prove debilitating to artists and being such a subjective problem it has led to the search for an empirical way to prove Quality in art (such as The Venetian Secret Hoax).

Clement Greenberg stated that art is always tied to money, as a luxury item this is hard to dispute. The more expensive a work of art, the more renowned it becomes and therefore the more influential. Strangely, Perry notes, that in the gallery situation, pieces are often priced according to their size, although this factor is removed by the time the work reaches the secondary market.

So, if the value of a work of art is an unreliable indicator of its quality, what remains?

Here Perry raises the important issue of Validation. As a scientific paper undergoes peer review before journal publication, so a work of art is first validated by peer review before being placed in a gallery. The status of this gallery is of great importance and is enhanced by Validation from serious critics and then collectors and dealers, dealers themselves being one of the important factors in this process as their reputation dictates the placing of the work for sale and the likelihood of it being picked up by a serious collector, thus adding kudos to the work of the artist.

Finally the public have the chance to Validate the work. Numbers of visitors to a show are measurable and an important source of information available to curators, perhaps one of the single most important. Gallery and museum curators decide what goes onto display to the general public and this over time should help to stabilise the prices for an artist, thus giving collectors more confidence in their investments. With humour, Perry notes that bank vaults are stuffed with Silver, Wine, Art and Gold (S.W.A.G.).

To finish this study of quality and validation, Grayson Perry, notes that Political Art is largely outside of this process. If the message is agreed with by enough people, they will enjoy the message of the art. It is interesting to consider how many artists keep their political and artistic endeavours entirely separate. He ends this first lecture with a quote from Alan Bennett "you don't have to like it all".

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Frieze Art Fair London 2013

Although completely overwhelming, the enormous tent that is Frieze contains many wonders of the world. Somethings stop you in your tracks by virtue of surprise, amazement or bewilderment. My personal low point consisted of four people standing beneath a black sheet; they had head holes but I spent more time contemplating my very reasonably priced sandwich (it's the drinks that hammer one's pocket). My high point was a series of miniature sculptures made of cardboard and plastic. Other people will have very different opinions and that is the joy of the sheer vastness and variety that is Frieze. Also, Frieze cannot be done in a day and I was there for around four hours so I can only present very edited highlights.

Sou Fujimoto, a Japanese architect (born 1971) designed the temporary Serpentine gallery Pavilion in London. His miniature models of architectural space were fascinating, drawing the viewer in close and having an almost weightless quality.

An amazing explosion of colour and skill was demonstrated by an artist selected by the Tina Kim Gallery, New York. This eye catching North Korean hand embroidery on silk by KyungA Ham (b. 1971) had many passers by stop.

Entitled Greed is Good, the pattern was so dynamic that it took a closer inspection to believe it was a hand embroidery.

The Egyptian born artist, Wael Shawky (b.1971) and represented by the Sfeir-Semler Gallery of Hamburg and Beirut, is mostly known for his videos of mythical journeys, featuring some animation and puppetry. Two of the marionettes from his Cabaret Crusades to Cairo were displayed. Made of ceramic, wood and paint, the two characters were very charismatic and, in their glass cabinet, invoked the activity of their journey.

The Johan Berggren Gallery displayed the "creative debris" of artist Ryan Siegan-Smith (b. 1982) who has worked under various names, including Leeroy the Duck and Allen Mothchart. He works by accumulating visual aide-memoirs in order to recall number sequences using mnemonic techniques. Although the numerical sequence itself seems somewhat irrelevant, it is the celebration of the techniques of the type of mind which wants to learn such sequences wherein lies the interest. There is no way of discerning which visual clues relate to which numbers, but the very fact that they have working significance to an individual encourages contemplation.

Johanna Calle (b. 1965) selected by Casas Riegner produces works based on her native Colombia and the fragility of the environments. The series Conflicted Land is composed of pictures of trees native to Colombia, the photos being cut out from aerial photos which are taken to police the growth and illegal felling of these precious resources. The images are simple and engaging but it is not too far a stretch to relate to the social and political issues she tries to emphasise.

Working in film and photography, one of the most arresting displays was that of Marcus Coates (b.1968), selected by Kate MacGarry. His very high resolution prints onto rice paper of animals were superb. What raised then above the standard of fascinating photography or animal portraiture was the way in which they had been made three dimensional. Not only was there a fantastic depth to the photos and the colours themselves, but the paper had been creased and crinkled into sculptural forms which emphasised the shape of the subject matter. Thus a photo of an ostrich became a 3D sculpture of a picture of an ostrich, an effect which continued whilst looking down the side of the print.

Korean artist Yeesookyung (b. 1963) has many varied pieces in the Saatchi Gallery all following the theme of the Translated Vase. By using broken ceramics and reassembling them into a completely different form, she draws on the Japanese tradition of 'fixing' broken ceramics, using precious metals, so that the vessel is not only made stronger but so that the repair becomes part of the history of the vessel. I didn't find that Yeesookyung quite achieved this resonance. The parts of the vessel were too obviously broken to create a matching set (colour, design, size) and they were cemented together, the join then being over-painted by 24kt gold. This was imprecisely done and highlighted to me the gulf between Yeesookyung's work and the fine craftsmanship of the traditional inspiration.

There were some standard favorites represented at Frieze, including Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami, which were great fun to see, although already familiar and recognisable at twenty paces. New to me was the work of Tony Cragg (b. 1949) the 1988 Turner Prize winner. I was enchanted by his sandstone-esque sculpture, made from metal and seemingly beyond scale. He is an artist I will enjoy investigating further.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sir Anthony Caro

One of the 20th century's most influential British sculptors has died of a heart attack as he approached his ninetieth birthday.

Likened by many to Henry Moore, a generation before him, for his worldwide influence, Caro first came to the art world's attention in 1963 at the Whitechapel Gallery His 1963 sculpture Early One Morning was an abstract, brightly coloured sculpture which showed Caro's background in engineering and put forward a new movement in how sculpture was presented.

Sir Anthony Caro was the recipient of many prizes, including the Lifetime Achievement Award in sculpture. He was knighted and given the Order of Merit and was the subject of a 2005 Tate Britain Retrospective.

Interestingly, he was also one third of the design team behind London's Millennium Bridge.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Reith Lectures 2013

Playing to the Gallery by Grayson Perry.

I have been following the career of Grayson Perry since the very moment I saw him on television in the early nineties. I was a schoolgirl, attending a convent school in a Cheshire village and contemporary art was not part of my life.

I saw Grayson Perry, as Claire, accepting the Turner Prize (of which I had never heard) and a different side of what might be sensible appeared to me. It wasn't a conscious decision to follow Mr Perry and it is only in recent years that I have gone out of my way to seek out his work, his exhibitions, but whenever he was mentioned I was interested.

He is a fascinating man. He has the confident authority of most successful artists, but he always seems to be lacking the arrogance of many of his peers. He might be odd, he might be married to his psychoanalyst, he might be many things, but I believe that he is a fascinating and humorous man ans I was was delighted when I heard he would be giving this year's series of Reith Lectures.

The following is not a transcript of the lectures but a summary of what I gain from listening to them.

1. Democracy has bad taste.

Grayson Perry inhabits the Art World. As an artist and lecturer and commentator on contemporary arts, he does not consider himself an expert but must indeed be a close approximation.

As an insider of the this rarefied world and in giving these lectures he tries to encourage people to engage with physical places where art is to be to found and to be comfortable.

Speaking primarily with regard to the visual arts, Grayson Perry considers museums, commercial galleries and the more introspective, historical artist-dealer-collector relationship. He dissects the 5.3million visitors per annum to the Tate Modern, one of the U.K.s most popular tourist destinations. These visitors have been split into categories, some of whom, Grayson argues, would be impossible to keep away and these include the 'Urban Arts Eclectic' and the 'Mature Explorers', but he addresses himself to the 36% of visitors categorised as 'Dinner and a Show' or 'Fun, Fashion and Friends'.

During the discourse, Insider, Mr Perry, recognises the intimidating nature of the gallery environment and tries to address this by providing the imagined visitor with a methodology of approaching the art to which they will be exposed and how to judge it on an alien scale of merit.

The issues of judging art and of deciding upon its quality are addressed as one and the same things, in most respects. For example the popularity of a piece of art does not mean it is of quality but an historically significant piece or one of aesthetic sophistication may become very popular and therefore valuable and will inevitably be of quality.

As humans looking at art we will all have many similar responses and many of these can be cultural. Several Russian artists surveyed the preferences of the public, across several countries, as regards contemporary art and discovered that most people prefer the colour blue. This is of course of no help to anyone but it is interesting nevertheless.

There is a language which surrounds the discussion of art which may be alienating to the general public and also unhelpful to artists themselves. An analysis of the website of art gallery press releases E Flux showed it contained very few nouns; Art English. This is a In the hundred years leading up to the 1970s, Grayson Perry argued, art became very self-conscious. This could prove debilitating to artists and being such a subjective problem it has led to the search for an empirical way to prove Quality in art (such as The Venetian Secret Hoax).

Clement Greenberg stated that art is always tied to money, as a luxury item this is hard to dispute. The more expensive a work of art, the more renowned it becomes and therefore the more influential. Strangely, Perry notes, that in the gallery situation, pieces are often priced according to their size, although this factor is removed by the time the work reaches the secondary market.

So, if the value of a work of art is an unreliable indicator of its quality, what remains?

Here Perry raises the important issue of Validation. As a scientific paper undergoes peer review before journal publication, so a work of art is first validated by peer review before being placed in a gallery. The status of this gallery is of great importance and is enhanced by Validation from serious critics and then collectors and dealers, dealers themselves being one of the important factors in this process as their reputation dictates the placing of the work for sale and the likelihood of it being picked up by a serious collector, thus adding kudos to the work of the artist.

Finally the public have the chance to Validate the work. Numbers of visitors to a show are measurable and an important source of information available to curators, perhaps one of the single most important. Gallery and museum curators decide what goes onto display to the general public and this over time should help to stabilise the prices for an artist, thus giving collectors more confidence in their investments. With humour, Perry notes that bank vaults are stuffed with Silver, Wine, Art and Gold (S.W.A.G.).

To finish this study of quality and validation, Grayson Perry, notes that Political Art is largely outside of this process. If the message is agreed with by enough people, they will enjoy the message of the art. It is interesting to consider how many artists keep their political and artistic endeavours entirely separate. He ends this first lecture with a quote from Alan Bennett "you don't have to like it all".

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Frieze Art Fair London 2013

Although completely overwhelming, the enormous tent that is Frieze contains many wonders of the world. Somethings stop you in your tracks by virtue of surprise, amazement or bewilderment. My personal low point consisted of four people standing beneath a black sheet; they had head holes but I spent more time contemplating my very reasonably priced sandwich (it's the drinks that hammer one's pocket). My high point was a series of miniature sculptures made of cardboard and plastic. Other people will have very different opinions and that is the joy of the sheer vastness and variety that is Frieze. Also, Frieze cannot be done in a day and I was there for around four hours so I can only present very edited highlights.

Sou Fujimoto, a Japanese architect (born 1971) designed the temporary Serpentine gallery Pavilion in London. His miniature models of architectural space were fascinating, drawing the viewer in close and having an almost weightless quality.

An amazing explosion of colour and skill was demonstrated by an artist selected by the Tina Kim Gallery, New York. This eye catching North Korean hand embroidery on silk by KyungA Ham (b. 1971) had many passers by stop.

Entitled Greed is Good, the pattern was so dynamic that it took a closer inspection to believe it was a hand embroidery.

The Egyptian born artist, Wael Shawky (b.1971) and represented by the Sfeir-Semler Gallery of Hamburg and Beirut, is mostly known for his videos of mythical journeys, featuring some animation and puppetry. Two of the marionettes from his Cabaret Crusades to Cairo were displayed. Made of ceramic, wood and paint, the two characters were very charismatic and, in their glass cabinet, invoked the activity of their journey.

The Johan Berggren Gallery displayed the "creative debris" of artist Ryan Siegan-Smith (b. 1982) who has worked under various names, including Leeroy the Duck and Allen Mothchart. He works by accumulating visual aide-memoirs in order to recall number sequences using mnemonic techniques. Although the numerical sequence itself seems somewhat irrelevant, it is the celebration of the techniques of the type of mind which wants to learn such sequences wherein lies the interest. There is no way of discerning which visual clues relate to which numbers, but the very fact that they have working significance to an individual encourages contemplation.

Johanna Calle (b. 1965) selected by Casas Riegner produces works based on her native Colombia and the fragility of the environments. The series Conflicted Land is composed of pictures of trees native to Colombia, the photos being cut out from aerial photos which are taken to police the growth and illegal felling of these precious resources. The images are simple and engaging but it is not too far a stretch to relate to the social and political issues she tries to emphasise.

Working in film and photography, one of the most arresting displays was that of Marcus Coates (b.1968), selected by Kate MacGarry. His very high resolution prints onto rice paper of animals were superb. What raised then above the standard of fascinating photography or animal portraiture was the way in which they had been made three dimensional. Not only was there a fantastic depth to the photos and the colours themselves, but the paper had been creased and crinkled into sculptural forms which emphasised the shape of the subject matter. Thus a photo of an ostrich became a 3D sculpture of a picture of an ostrich, an effect which continued whilst looking down the side of the print.

Korean artist Yeesookyung (b. 1963) has many varied pieces in the Saatchi Gallery all following the theme of the Translated Vase. By using broken ceramics and reassembling them into a completely different form, she draws on the Japanese tradition of 'fixing' broken ceramics, using precious metals, so that the vessel is not only made stronger but so that the repair becomes part of the history of the vessel. I didn't find that Yeesookyung quite achieved this resonance. The parts of the vessel were too obviously broken to create a matching set (colour, design, size) and they were cemented together, the join then being over-painted by 24kt gold. This was imprecisely done and highlighted to me the gulf between Yeesookyung's work and the fine craftsmanship of the traditional inspiration.

The

work of Elaine Sturtevant (b. 1930), selected by Gavin Brown's

enterprise, was interesting as it was unlike anything else I

encountered. It was understated and simple and did not seem to be

'trying'. The basis of Sturtevant's work is repetition but subtle

changes she applies to her work mean each piece is unrepeatable, for

example, her hand-pulled black and white photography.

Li

Songsong (b. 1973) selected by Pace, has a fascinating collage,

multi-canvas style. It invites inquiry. It is a whole made of

harmonious and yet overlapping components. The colours are wrong, the

style is coarse and there is an element of the random thrown in, but the

whole resolves into an almost photographic image. When he paints a

person, the result is portrait like, even if each thickly painted canvas

is difficult to resolve.There were some standard favorites represented at Frieze, including Damien Hirst and Takashi Murakami, which were great fun to see, although already familiar and recognisable at twenty paces. New to me was the work of Tony Cragg (b. 1949) the 1988 Turner Prize winner. I was enchanted by his sandstone-esque sculpture, made from metal and seemingly beyond scale. He is an artist I will enjoy investigating further.

Tony Cragg

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sir Anthony Caro

One of the 20th century's most influential British sculptors has died of a heart attack as he approached his ninetieth birthday.

Likened by many to Henry Moore, a generation before him, for his worldwide influence, Caro first came to the art world's attention in 1963 at the Whitechapel Gallery His 1963 sculpture Early One Morning was an abstract, brightly coloured sculpture which showed Caro's background in engineering and put forward a new movement in how sculpture was presented.

Sir Anthony Caro was the recipient of many prizes, including the Lifetime Achievement Award in sculpture. He was knighted and given the Order of Merit and was the subject of a 2005 Tate Britain Retrospective.

Interestingly, he was also one third of the design team behind London's Millennium Bridge.

Paper Wink (1999/2002)

handmade paper, aluminum and wood

Anthony Caro

Anthony Caro

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Drawing.

Journey.

Before

photography, drawing and painting were the only means of recording a

scene or an image accurately. For this purpose drawing can be

extrapolated to include the processes leading up to the production of

prints in earlier times.

Now, with the benefit of the photographic discipline, drawing has expanded its application.

It is still of the utmost importance to have a grasp of the fundamentals of good drawing practice, through life drawing and still-life, as this skill underpins much of the creative processes of sculpture and design; however, drawing can be free from the constraints of gravity and so has, some could argue, a more liberated approach to creativity. It also informs the artist as to what they are distorting from reality as it is an education in perspective and correct proportion.

Selected Life Drawings by Kathryn Moores. Charcoal and paper 2013.

Selected Life Drawings by Kathryn Moores. Charcoal and paper 2013.

The concept of Journey as a drawing project is very broad.

The artist Mark Bauer (1975) uses the traditional black and white look of photography to record his journeys to different places, for example, a Sanatorium.

HB Sanatorium Kreuzlingen Schloss Bellevue 1988 Mark Bauer

It is still of the utmost importance to have a grasp of the fundamentals of good drawing practice, through life drawing and still-life, as this skill underpins much of the creative processes of sculpture and design; however, drawing can be free from the constraints of gravity and so has, some could argue, a more liberated approach to creativity. It also informs the artist as to what they are distorting from reality as it is an education in perspective and correct proportion.

The concept of Journey as a drawing project is very broad.

The artist Mark Bauer (1975) uses the traditional black and white look of photography to record his journeys to different places, for example, a Sanatorium.

HB Sanatorium Kreuzlingen Schloss Bellevue 1988 Mark Bauer

pencil and paper

I

cannot view the destination of a journey as being the same as a

journey; this being a necessity for any human wishing to visit

anywhere. In the past I have traveled with an unusual companion, a toy

of my daughter's, in order that she might feel connected to my having

traveled. These inanimate teddy bears took on a superb preciousness

whilst traveling, such was my concern at losing them, and their

appearance in souvenir photographs lend a particular sense of the

personal to otherwise generic scenes.

Green Bear on the Isle of Wight Ferry for Cowes week 2013

Kathryn Moores

Another way of approaching this concept of taking items for a journey is in the most basic; what do we normally take on a journey but our suitcase? The personal items are contained within the suitcase (unless they are as precious as the above and must be kept in hand luggage all the time).

Komi Tanaka took a suitcase on a journey to Rome and photographed the suitcase in various locales. These pictures, referenced to a tourist map, and displayed alongside the adventurous suitcase, formed an installation at Frieze 2013.

Komi Tanaka We Found Something When We Lost Other Things 2012 unannounced action

The return address on the suitcase as it was left on corners in Rome was always the gallery where Komi Tanaka was exhibiting, hence it was also advertising for his show and a commercial endeavour. I would have been interested in the record of interactions of the public with this 'abandoned' suitcase in these days of terror alerts and fears of abandoned bags. This is why I prefer to travel with a teddy bear.

Drawing can always, an this is the most important factor besides recording things for posterity, enter the realms of the unreal. The abstract, the multi-coloured, the distorted; all of these are the everyday of contemporary drawing. Colour is the main feature in the works of Chadwick Rantanen (American 1981), for example, whether he is working in sculpture, installation or drawing.

Multicoloured drawing by Chadwick Rantanen above carbon fibre Loop. Frieze 2013.

Drawings from the imagination appeal to my aesthetic as photo quality reproductions of a scene seem to be outdated.

An imagined journey, with similarities to the disbelieved journey of the Venetian Marco Polo (1254 - 1324) who introduced the Europeans to the cultures of Asia and China and was widely discredited as preposterous, seems a likely drawing project. Even today, with his inclusion of some facts (paper money) and the omission of others (Chinese foot binding practice) there is no consensus as to whether Polo ventured on his journey or simply compiled his narrative from hearsay.

The act of traveling on a journey gives a sense of movement which might be interestingly caught by the discipline of drawing. The blurred exterior passing by the high speed train carriage window, where the train is given a sense of immobility and all motion is external. The characters in the carriage also become important, absorbed in their own journeys and making it a solitary and yet communal undertaking. .

Kathryn Moores

Another way of approaching this concept of taking items for a journey is in the most basic; what do we normally take on a journey but our suitcase? The personal items are contained within the suitcase (unless they are as precious as the above and must be kept in hand luggage all the time).

Komi Tanaka took a suitcase on a journey to Rome and photographed the suitcase in various locales. These pictures, referenced to a tourist map, and displayed alongside the adventurous suitcase, formed an installation at Frieze 2013.

Komi Tanaka We Found Something When We Lost Other Things 2012 unannounced action

The return address on the suitcase as it was left on corners in Rome was always the gallery where Komi Tanaka was exhibiting, hence it was also advertising for his show and a commercial endeavour. I would have been interested in the record of interactions of the public with this 'abandoned' suitcase in these days of terror alerts and fears of abandoned bags. This is why I prefer to travel with a teddy bear.

Drawing can always, an this is the most important factor besides recording things for posterity, enter the realms of the unreal. The abstract, the multi-coloured, the distorted; all of these are the everyday of contemporary drawing. Colour is the main feature in the works of Chadwick Rantanen (American 1981), for example, whether he is working in sculpture, installation or drawing.

Multicoloured drawing by Chadwick Rantanen above carbon fibre Loop. Frieze 2013.

Drawings from the imagination appeal to my aesthetic as photo quality reproductions of a scene seem to be outdated.

An imagined journey, with similarities to the disbelieved journey of the Venetian Marco Polo (1254 - 1324) who introduced the Europeans to the cultures of Asia and China and was widely discredited as preposterous, seems a likely drawing project. Even today, with his inclusion of some facts (paper money) and the omission of others (Chinese foot binding practice) there is no consensus as to whether Polo ventured on his journey or simply compiled his narrative from hearsay.

The act of traveling on a journey gives a sense of movement which might be interestingly caught by the discipline of drawing. The blurred exterior passing by the high speed train carriage window, where the train is given a sense of immobility and all motion is external. The characters in the carriage also become important, absorbed in their own journeys and making it a solitary and yet communal undertaking. .

No comments:

Post a Comment